Parsifal

“I suppose I know better than any one else the prodigies of which Wagner was capable, the fifty worlds of strange ecstasies to reach which no one but he had wings strong enough; and as I am today sufficiently powerful to turn even the most dubious and dangerous things to my own advantage, and thus to grow more powerful, I name Wagner as the greatest benefactor of my life. (…) The fact that we have suffered greater agony, even at each other’s hands, than most men of this century are able to bear; will associate our names forever.”[i]

Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, 1889

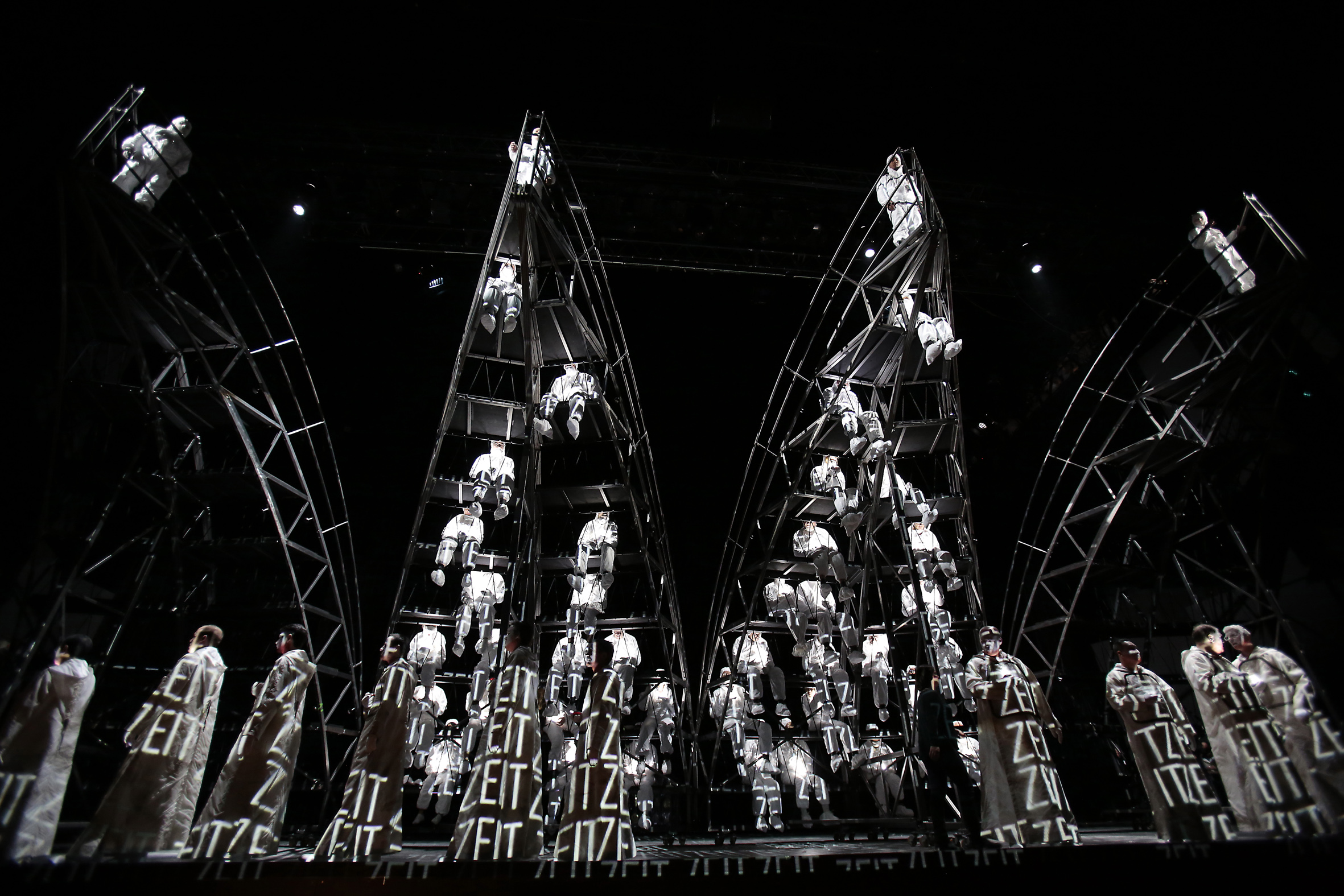

The close friendship and subsequent estrangement between Wagner and Nietzsche play a very important role in our proposal. The ambiguity in the music of Parsifal reflects the connection with Nietzsche’s text, as though its visual representation were enwound in the viscerality of Wagnerian music. Parsifal incarnates the extreme moral indetermination of contemporary man. Western culture has not yet solved the conflict between instinct and rationalism, ritual and liturgy. To Wagner, the Good Friday ceremony in the last act is a festive celebration of regeneration, like the Greek Dionysiaca. The end of Parsifal suggests not Christian redemption, but a pagan ritual, an experience by which audience and actors will participate in the same ceremony that will revive their commitment to their communitarian lives. In our proposal, Gurnemaz, the narrator, thus becomes a baker of bread, namely a bread that grows organically throughout the representation. At the end, bread will be given to the people present so as to celebrate the renovated communitarian ritual.

In Parsifal, the Brotherhood of the Knights of the Grail, which may only be joined by those who are willing to renounce themselves, is in danger of internal disintegration. Its carefully constructed world, based upon the knights’ strict rules, is decaying. The social hierarchy of Montsalvat is tumbling. Its founder, Titurel (Richard Wagner’s alter ego) is a living corpse and Amfortas, the leader, is suffering from an incurable wound (Nietzsche and his permanent neuralgias). His disturbing open wound, whose blood flows periodically like a menstruation, is the living intrusion of everything Dionysiac or instinctive into the life of the suffering knight, all efforts to cure him notwithstanding. Amfortas’s character incarnates the painful imbalance of the modern subject, dispraiser of everything irrational. He succumbed to Klingsor, the magician (Nietzsche and his mental illness), who is the main enemy of the community. Amfortas thus lost the sacred spear to Klingsor and as he was unable to resist the erotic flowermaidens, the sweet and enticing inhabitants of Klingsor’s magic garden, a realm which will devour those who enter it and make them slaves of its delights.

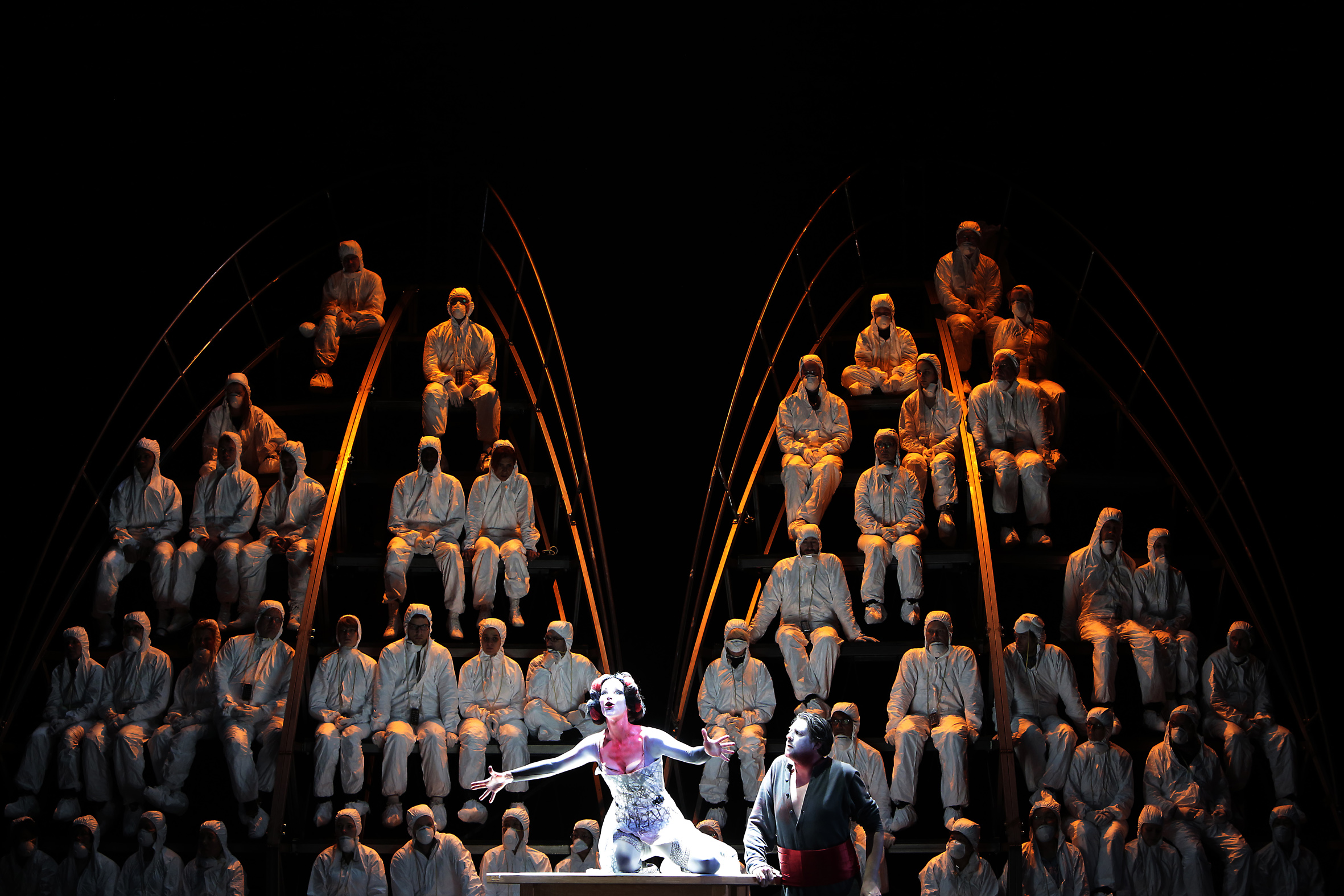

This community in crisis had been established by Titurel so as to guard two sacred relics: the grail (sacred vagina) and the spear (sacred phallus). The two can be understood to be related to the Hindu bond, as a sign of the two integrated sexes that represent the regeneration of the universe. They live in waiting, hoping for a stranger to cure Amfortas’s wound, so that he can recuperate the spear, guard the grail and repair the errors of the past whilst repeating the ritual forever more, even though it has lost its meaning. Then appears Parsifal, a foolish and pure lad, whom knight Gurnemanz invites to a long inaugural journey. Perhaps this cheerful lad with no past will free them from their sorrow.

The path for which Parsifal is setting off, or Middle Path, as it is called in Buddhism, avoids extremes of excesses and privations, as they unleash the emotional avidity inside us. Parsifal, who shares many similarities with Siegfried, another of Wagner’s heroes, is the only one who is aware from the beginning, even before his transformation through Kundry’s kiss, that Klinsor’s magic garden is unreal, when he asks himself if this is a dream.

Kundry plays a key role in the development of Parsifal. She symbolises eternal femininity, a woman who, in the first act, rebels against her condition as woman, while in the second act, she serves Klingsor, the magician by seducing Parsifal. Finally, in the third act, she becomes Parsifal’s loyal companion, who accompanies him to the temple, or the place where all energies are united (the total work of art or Gesamtkunstwerk). This is the moment when the stage turns into a vessel or grail of knowledge. The mysterious Kundry, asleep in harmony with nature, will scream in agony or ecstasy, capable of transforming her desire for Parsifal into compassion towards humankind.

In Parsifal, there is much sorrow and resistance to oblivion. Parsifal, Kundry, Amfortas and Titurel all suffer. At the same time, in Montserrat, Parsifal encounters various characters who lack the capability to forget. Amfortas, for one, is obsessed with his recollection of the betrayal of the grail and Kundry too, is victim of her past. Peter Sloterdijik comments in his book Thinker on stage: Nietzsche’s Materialism, that to Nietzsche, somebody who can forget the past is somebody who can set free their creative energies. Only then when one can escape oneself is it possible to find oneself (the search for the self implies having to undertake a journey out of the self). Parsifal’s character is, in this sense, profoundly nietzschian. In our Parsifal, we show a common man who is searching for the path of full consciousness in order to “cure his wounds”, which were the product of human actions, lacking in any universal meaning. In our imagination, Parsifal is the übermensch, an androgyne, whose cells are terminals which connect with us through social networks.

In Parsifal, human nature is defined through desire, a humankind which suffers because its desires cannot be fulfilled. In this testamentary work by Wagner, however, desire is not defined as an individual’s sexual desire, but rather as the compassionate desire of a community or brotherhood. This desire is a destabilising force, for it demands freedom and autonomy for the contemporary man and at the same time a stabilising desire in that it is a social force. Any individual’s sensuality is transformed into a shared experience.

Parsifal finally embraces his destiny and becomes a wise man.

Conductor: Markus Stenz

Stage direction: Carlus Padrissa (La Fura dels Baus)

Set Design: Roland Olbeter

Costume: Chu Uroz

Video: Welovecode

Light: Andreas Grutas

Assistant staging: Tine Buise

Choreography assistant: Mireia Romero

Playwriting: Let George & Tanya Carnival

Chorus master: Andrew Ollivant

Gurnemanz: Matti Salminen

Parsifal: Marco Jentzsch

Amfortas: Boaz Daniel, Samuel Youn

Klingsor: Samuel Youn

Titurel: Young Doo Youn Park

Kundry: Dalia Schaechter

chorus Cologne Opera

and Gürzenich-Orchestra Cologne

Parsifal is certainly a work that has been dissected, which has attracted intellectuals, hated and loved. But it still remains an enigma. The contact points with The Birth of Tragedy Nietzsche are several, born of the same historical context and both question the most sacred principle of modernity: the dogma of the individual moral autonomy.